It decried a “wellbeing vacuum” in UK workplaces which was costing employers dear in absenteeism.Īn earlier CIPD report made the case that if employees felt they were working harder, it was not because they were working longer hours rather, the reason was that work was more demanding and intense. But why then, if we are working fewer hours than our grandparents and parents, do surveys paint a picture of British workers feeling exhausted and overloaded?Ī report last week from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) found many employees feel under “excessive pressure”, with “far too many people doing more work than they can cope with”. It’s comforting to think that despite fears that machines will take our jobs, what might actually happen is that they take some of our workload but leave us our livelihoods, as well as more leisure time. Weale takes the long view and points out that a typical week for a full-time worker is now just under 40 hours, compared with more than 60 in 1860. For example, there are now more older people in the workforce who do not want to retire, but nor do they want to work full-time. Her colleague on the monetary policy committee, Martin Weale, makes a link to demographics. She believes much of this reflects a choice by workers. BoE policymaker Kristin Forbes noted in a recent speech that people are working fewer hours on average than they were before the crisis. Britain’s working week then lengthened again, but recently that improvement has stalled. Many employers cut hours to match slower demand rather than lay off workers altogether during the recession.

The Bank of England is among those highlighting the fact that the average number of hours worked per week has been falling in the UK. In more recent times, there are signs the staff at Agent Marketing are not alone in working a shorter week. He calculates that the week’s output was slightly higher when the munition workers worked 48 hours over six days, compared with 70 hours over seven days. It was a smart move, says Pencavel, writing in the December 2015 issue of the Economic Journal.

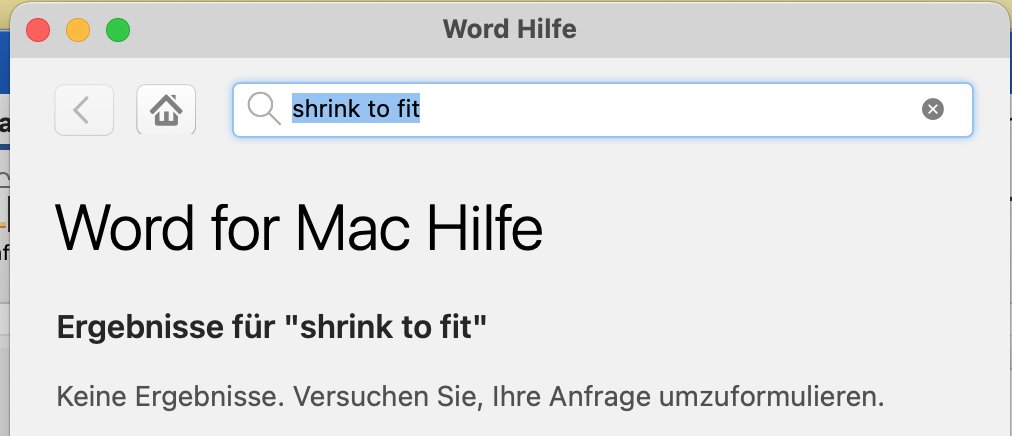

THE OPPOSITE OF SHRINK TO FIT IN WORD FULL

The committee’s recommendations included giving workers at least one full day off each week. He revisited data collected by the health of munition workers committee, set up by war minister David Lloyd George, to investigate the effect of long working hours on the factories’ predominantly young female workers. A government decision to cut hours at munitions plants during the first world war made workers healthier and also more productive, according to research by John Pencavel, a professor of economics at Stanford University. The trailblazers for the six-hour day hail from Sweden, where a variety of companies have cut their working week to improve wellbeing and as a result have reported improvements in productivity and lower staff turnover.Įvidence that shorter hours can boost output has been around much longer. Corcoran says hours will be down overall compared with pre-experiment days and productivity is up. Every employee will do a six-hour day at least once a week and on Friday everyone finishes at 4pm. The 14-strong workforce has cut daily meetings from one hour to 15 minutes and canned Friday’s meeting altogether.

THE OPPOSITE OF SHRINK TO FIT IN WORD TRIAL

In an office where clients are accustomed to their calls being answered until 6pm, it just doesn’t make business sense.īut the trial has still shaken things up. It will not be introducing those hours on a permanent basis, says managing director Paul Corcoran. Now the experiment is over and Agent Marketing is weighing the costs and benefits of a six-hour day. What started as a week-long challenge set by the BBC’s The One Show was extended throughout December and January. Its old 8.30am-5.30pm working day was swapped for 9am-4pm with a mandatory one-hour lunch break in the middle. A marketing agency in Liverpool has been trying just that for the last two months.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)